Last year, 2023, was The European Year of Skills. Its purpose was to address skills shortages and promote reskilling and upskilling. It is also intended that workers acquire the right skills to access quality jobs. Such aims are laudable and extend the strong and continuous emphasis on the importance of skills by the European Commission. However, policy on management is also needed.

Skills policy after skills policy

Every few years, the Commission launches another skill policy, championing different types of skills as the solution to the productivity, economic growth and competitiveness challenges facing Europe. Some of these policies look remarkably like old policies reheated. It seems that, like buses, if one waits long enough, the same skills policy comes around again. Nevertheless, whichever policy is being promoted at any given time, there is one thing that remains the same – the importance placed on the supply of skills. The assumption is that if workers acquire enough skills through training and education, these skills will magically lead to them acquiring good jobs and improve company performance in Europe. The fact is that after at least 30 years of the European Commission and its predecessors championing skills, it is unlikely that companies have yet received the memo that skills are important and skills acquisition needs to be encouraged. Some companies already train their workers or hire new workers because they need more skills, some companies don’t.

Skills policy alone is not sufficient: skill acquisition and skill use are important

We can’t simply keep throwing skills policies at Europe’s problems, especially not those based on supply-side actions. If enough good jobs don’t exist or employers don’t need more skills, then training and education can go to waste. Indeed, more workers report having under-used skills at work than employers report experiencing skill shortages. It’s not just skill acquisition that’s important but also skill use in work. The problem is that we don’t follow through and ensure that the skills acquired by workers are used in their work. Skills policies are important but not sufficient.

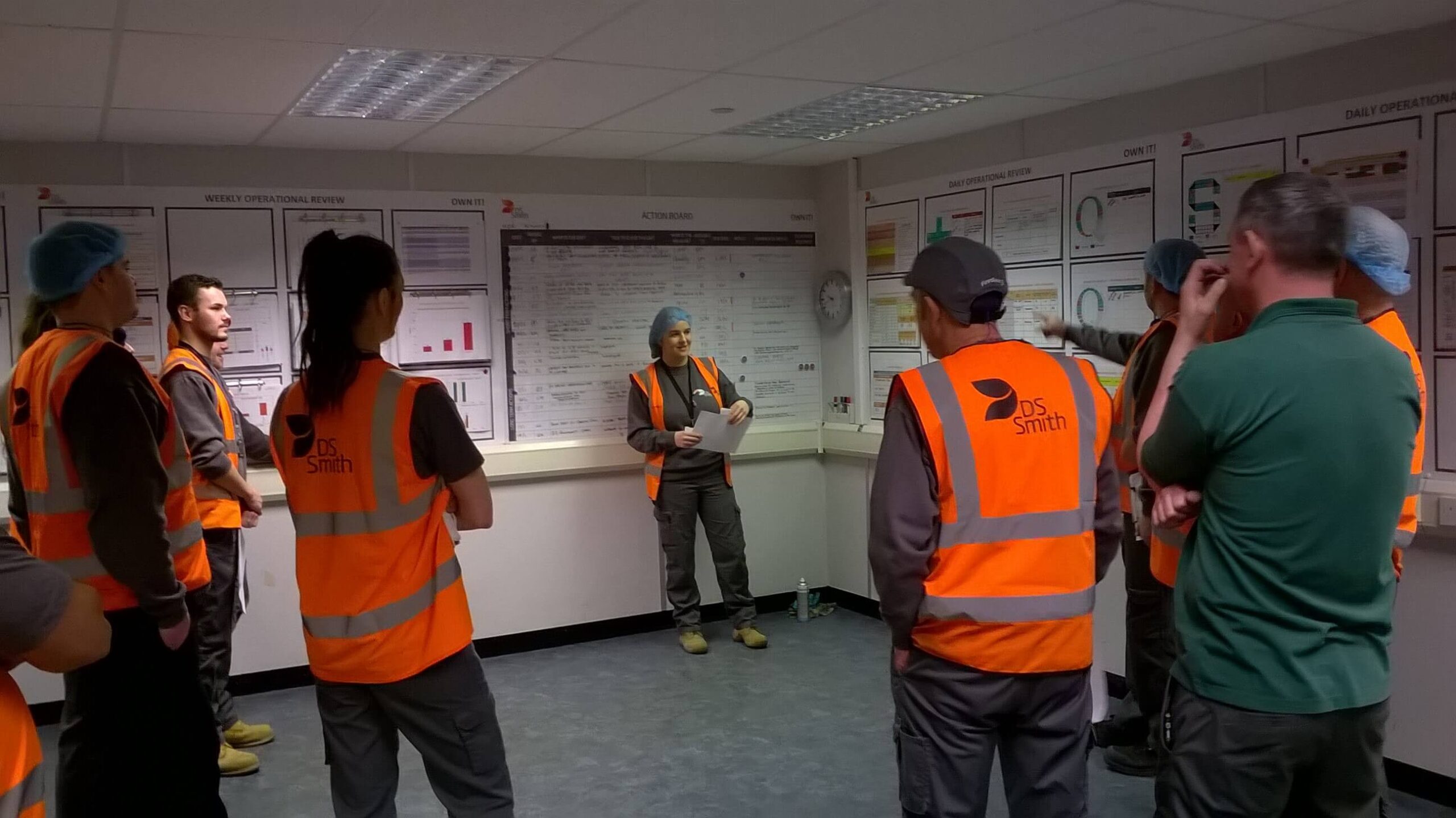

The management of workers at the firm level matters

We need to focus on those companies that don’t want or use more skills. We need to understand why they have little demand for more skills, either not training their workers more or not fully using the skills that their workers already possess. In this regard the management of workers matters. To understand why some companies are not maximising their potential, we need to look inside these companies – at their management – both as a group of people (managers) and what they do (management as a process). We know that there is good management practice in Europe. We also know from a raft of research that the quality of managers and the types of management vary across countries. And yet there is a reluctance on the part of the Commission to lift the lid on what happens inside companies that are under-performing and help them improve their management. Firm level management matters if the benefits of workers’ skills are to be realised.

A decade ago, Skills Australia (2012a and 2012b) reviewed the available research and concluded that better skills use occurs in companies with what looks a lot like good human resource management, with the dual outcomes of good jobs and better company performance, including fewer recruitment problems. Other research (Appelbaum et al., 2020) shows that workers need to have a combination of the ability (skills acquired through training and education) and, importantly, the opportunity in their work and the motivation to use those skills. Some types of management provide these opportunities and offer that motivation, other types don’t. Significantly, under the right type of management, the outcome is that workers put more effort into their work, again boosting company performance.

A management policy is required in Europe to complement skills policy

For years, the Commission has promoted skills policies with varying degrees of success. To complement skills policies, Europe also needs a management policy. This management policy should explicitly name the problem, aim to raise the quality of managers and draw upon good management practices, particularly concerning how workers are managed.

Research funded by the European Commission already provides substantial evidence on the effectiveness of various management styles. Drawing on this evidence base, and collaborating with trade unions and human resource professionals, the new management policy should seek to identify effective management practices that deliver the organisational benefits of skills. It should actively promote the adoption and dissemination of these better management practices throughout EU companies of all sizes where it is not already present.

If the European Commission wants to improve company performance, it needs to improve management, not just skills. The Commission’s ability to set out desired skills in European companies can be replicated for management. The Commission should be equally clear about what types of management practices it would like to see inside European companies. The Commission’s skill policies prescribe better skills. Let’s have a European Commission management policy that prescribes better management. It should start preparing now and bravely declare that 2025 will be The European Year of Management.

Related articles

May 11, 2024